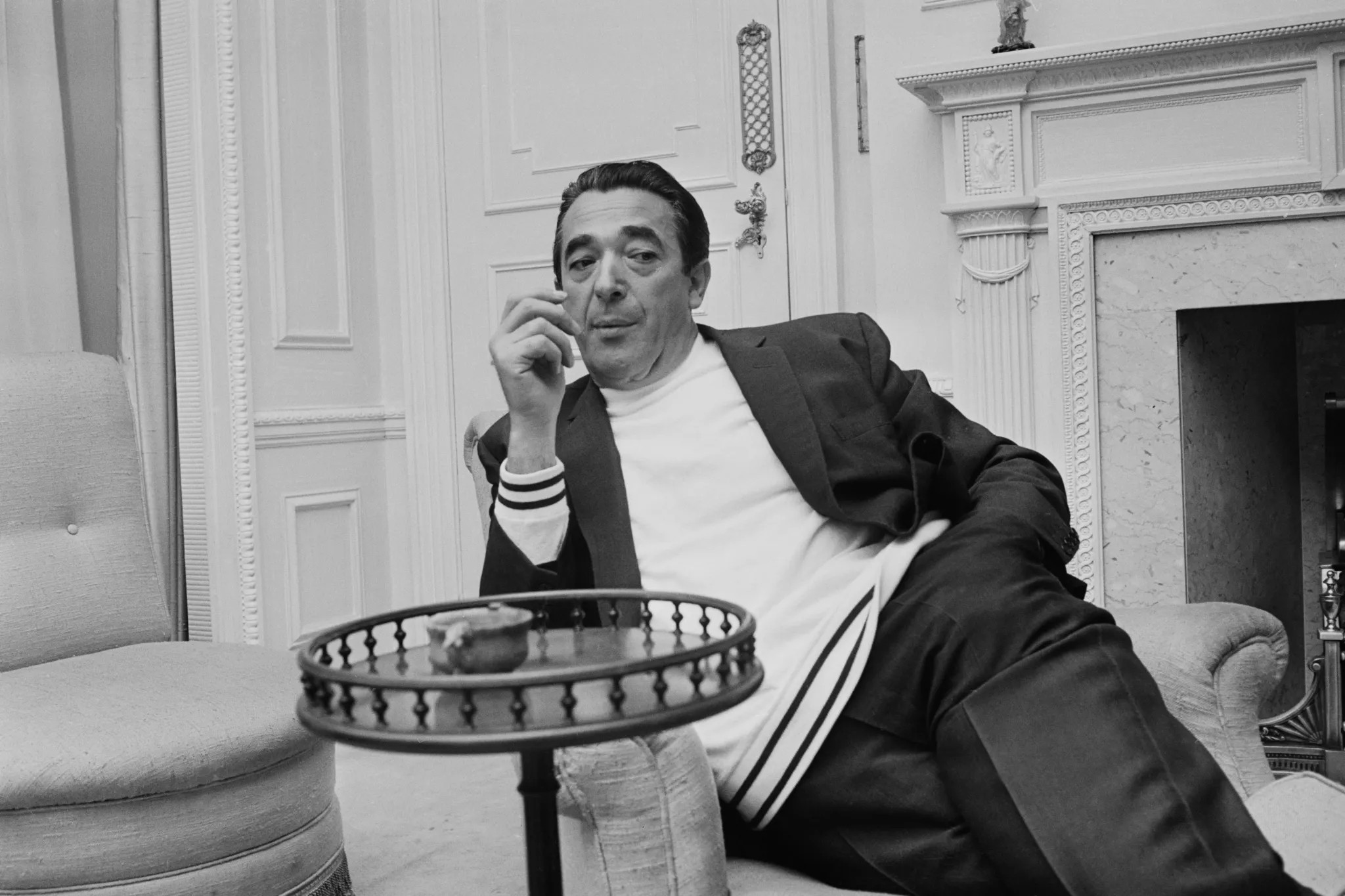

Sometime in May 1951.

Publishers of science can make profits far higher than most businesses because they are given their raw material (scientific studies) for free and yet that material is “must have” for customers, particularly academic libraries. What’s more success in academia depends on publishing in the journals owned by those publishers. This combination leads to science publishing being close to the Holy Grail of the greedy—“a licence to print money, a free lunch, or a magic money tree.” One of the first people to discover this Holy Grail was a man of great talent (or at least bombast) and few moral qualms: Robert Maxwell.

At the peak of his business empire, his net worth was $1.9 billion. After his death, his business empire was nearly $4 billion in debt. His companies included the Mirror group of newspapers, Maxwell Communications, Nimbus Records, P.F. Collier, Official Airline Guide, Prentice Hall Information Services, Macmillan publishing, the Berlitz language schools, and Pergamon Press, a technical publishing company.

⋮

In 1946, Robert Maxwell met Dr Ferdinand Springer, owner of the German Springer Verlag, Europe’s leading pre-war scientific publisher which was under financial burden due to the war. While still working at the Control Commission, Robert Maxwell became the director of a firm that offered distribution for Springers journals across Europe and the United States. In 1948, Butterworth Scientific Publications failed to take off and a joint company was created with its partner Springer Verlag, the new company was called Butterworth-Springer. In 1951, Robert Maxwell bought three-quarters of Butterworth-Springer and the remaining quarter was held by the former Springer Verlag scientific editor Paul Rosbaud. They changed the name of the company to Pergamon Press and rapidly built it into a major publishing house.

There followed protracted negotiations organized by Vanden Heuvel and, in May 1951, Butterworth agreed to sell its interest to Maxwell for £13,000. Agreeing also to a change of name to Pergamon Press, Butterworth set aside a considerable debt of £10,000.

As his official biographer, Joe Haines, acknowledge, this was ‘more money than Maxwell possessed at that moment, so he borrowed. He first went to Sir Charles Hambro.’ Who introduced Maxwell to Hambro varies with the different accounts. Haines says it was via the Board of Trade (BoT); Maxwell said it was Whitlock; Betty Maxwell claims it was Vanden Heuvel, Hambro’s business ‘fixer’. Whoever it was, the meeting gave rise to a City legend that Hambro had been so impressed by the forward-looking Maxwell and sufficiently persuaded of his business acumen that he ordered the chief cashier to give Maxwell a cheque book with authority to draw cheques up to a total of £25,000. In fact, the legend was no more than a cover story. The meeting certainly took place, but the matter of money had already been fixed by MI6.

— MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service, p. 141

Robert Maxwell was born as Ján Ludvík Hyman Binyamin Hoch on June 10, 1923 in Slatinské Doly in what was then Czechoslovakia [and is now Solotvyno, Ukraine]. His parents were poor Yiddish-speaking Orthodox Jews named Hannah and Mechel. Maxwell was one of seven siblings. During World War II, most of the family was murdered during Nazi occupation; Maxwell, however, had previously fled to France.

Here’s one that I just discovered. ‘Cause when you talk about science, people say, “Well, that might be true of politics, but that can’t be true of science because, I mean, we’ve got Ph.D. students, we’ve got university think tanks, we’ve got all these publications. How can they all be lying? Well, let me just tell ya. Here’s a little fun factoid. After World War II … I’ll just tell you the punch line, and then I’ll tell you how I got there. The intelligence services or the service created with Mossad, CIA, and MI6, they own all scientific and medical publishing.

What? Here’s how I discovered that. After World War II, Charles Dalton Darwin—he’s the grandson of Charles Darwin the explorer and Alexander Flemming who discovered penicillin. They got together and went to the British government. They said, “Hey, look what happened in World War II, the science. We would have been a lot better off had we been able to really communicate well. We need better scientific publishing around the world.”

And the British government, without consulting anybody, said, “No problem. We can do that.” And boom! Why could they do that? Because MI6 owned Buttersworth. MI6, being their equivalent of CIA. Buttersworth, the biggest medical scientific journal in the world. And it’s owned by their intelligence spy agency? Then, they combined it with the Germans.

And now, guess who they made—you can’t make this one up—the first editor-in-chief of the biggest now scientific publishing house in the world was Robert Maxwell. Robert Maxwell, who was provably a double agent. He worked for the British against the Germans in World War II. He was buried on the Mount of Olives, so he was a Mossad agent. But the claim to infamy is his daughter is Ghislaine Maxwell, pedophile consort of Jefferey Eppstein. It’s a cute club and we’re not in it. You have to control the narrative. You have to control publishing if you’re going to pull off The Truman Show of science, and they’ve done that.

It’s not just about [parasites as cause of cancer]. It’s about the PCR test. In The Truman Show, when he starts he’s in a false reality, this light falls from what he thinks is the sky, and it’s a stage light, almost hits him. He goes, “What? How can this be real?”

For me, that light was the PCR test. And it’s not just that the overcycled it. It’s that when I ran those sequences on the PCR test through the index of genetic, where these things come from, it didn’t show up SARS-COV-2, the virus they claimed. It showed up human genomes. Homo sapiens. There were 18 tests. I ran 12 of them, and then I gave up, and then I said, “Dear God! They’re testing to our own human genome.”

Sources:

- June 8, 2000. Stephen Dorril. MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. 1st edition. New York: Free Press.

https://www.amazon.com/MI6-Inside-Majestys-Intelligence-Service/dp/0743203798/.

Book. - November 5, 2002. Martin Dillon. Robert Maxwell, Israel’s Superspy: The Life and Murder of a Media Mogul. Carroll & Graf.

https://www.amazon.com/Robert-Maxwell-Israels-Superspy-Murder/dp/0786710780.

Book. - April 25, 2003. George Canning. “Robert Maxwell: A Spy Betrayed—But Whose Spy?” EIR Books, April 25, 2003.

https://larouchepub.com/eiw/public/2003/eirv30n16-20030425/eirv30n16-20030425_062-robert_maxwell_a_spy_betrayed_bu.pdf.

PDF. - June 7, 2019. Bridget, JC, and Jon Swinn. “Robert Maxwell, Promisgate, and the Advent of the Israeli Cybersecurity Industry.” Expose the Enemy.

https://www.exposetheenemy.com/robert-maxwell-promisgate-and-the-advent-of-the-israeli-cybersecurity-industry.

General Website Link. - July 12, 2019. Recluse. “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” VISUP.

https://visupview.blogspot.com/2019/07/maxwells-silver-hammer.html.

Blog. - August 3, 2020. Richard Hollick. “The Bouncing Czech.” Making Book.

https://rhollick.wordpress.com/2020/08/03/the-bouncing-czech/.

Blog. - February 9, 2021. John Preston. Fall: The Mysterious Life and Death of Robert Maxwell, Britain’s Most Notorious Media Baron. New York, NY: Harper.

https://www.amazon.com/Fall-Mysterious-Maxwell-Britains-Notorious/dp/0062997491/.

Book. - February 25, 2021. Jason Diamond. “Robert Maxwell, Not Rupert Murdoch, Was the Real-Life Logan Roy.” InsideHook.

https://www.insidehook.com/books/robert-maxwell-real-life-logan-roy.

General Website Link. - March 19, 2021. Richard Smith. “The Origins of Exploitative Science Publishing.” Richard Smith’s Non-Medical Blogs.

https://richardswsmith.wordpress.com/2021/03/19/the-origins-of-exploitative-science-publishing/.

Blog. - July 29, 2022. “Robert Maxwell Net Worth.” Celebrity Net Worth.

https://www.celebritynetworth.com/richest-businessmen/richest-billionaires/robert-maxwell-net-worth/.

General Website Link. - November 1, 2023. Stew Peters with Lee Merritt. Are Micro-Parasites the REAL Cause Of Cancer? Scientist SHILLS Censor Live Saving TRUTH. Stew Peters. Runtime: 18:39.

https://www.bitchute.com/video/NTCbzl2hTHzO/.

Video. - “Who Was Robert Maxwell? Everything You Need to Know.” In The Famous People.

https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/robert-maxwell-13892.php.

General Website Link. - “Robert Maxwell.” Spooky Connections.

https://www.spookyconnections.com/Robert-Maxwell.

General Website Link. - “Pergamon Press.” In Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Pergamon_Press.

Reference. - “Dr. Lee Merritt – The Medical Rebel.”

https://drleemerritt.com/.

General Website Link.